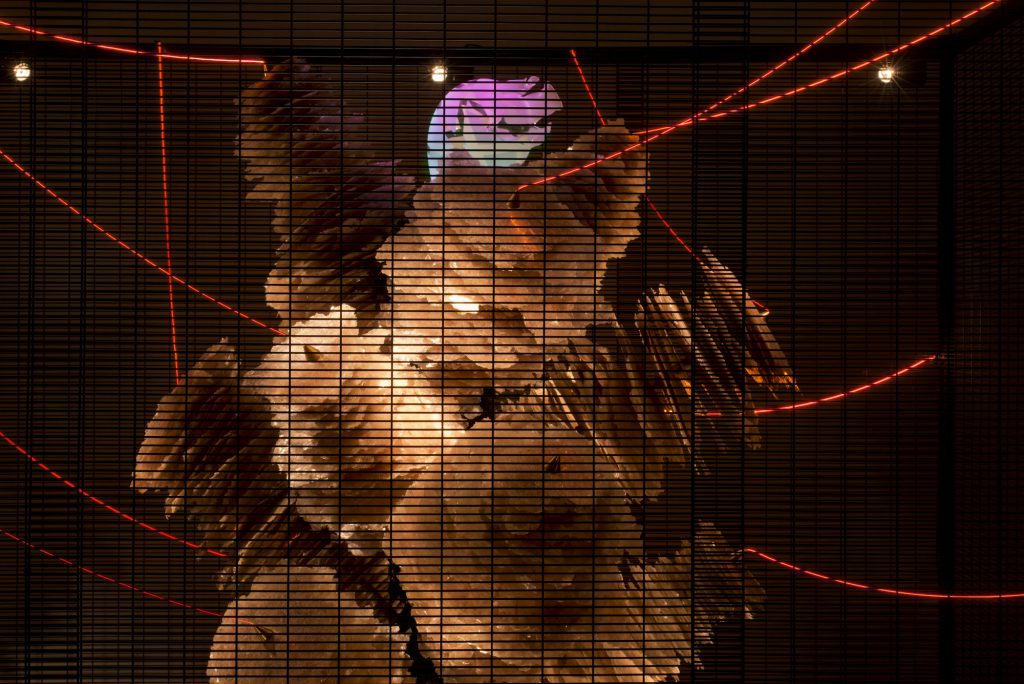

Liliane Lijn, Electric Bride, 1989, aluminum, steel, cock feathers, Elmflex micanite, brass, blown glass; 280 x 300 x 240 cm, courtesy the artist and Rodeo, London / Piraeus

Liliane Lijn, Electric Bride, 1989, aluminum, steel, cock feathers, Elmflex micanite, brass, blown glass; 280 x 300 x 240 cm, courtesy the artist and Rodeo, London / Piraeus

Born in New York in 1939 to a family of Russian Jewish émigrés, Liliane Lijn began her artistic trajectory in the late 1950s in Paris after encountering members of the city’s Surrealist circle, like the poet and alchemist Elie-Charles Flamand, and cultivating a fascination with Milarepa’s Buddhist poetry and Richard Feymann’s Lectures on Physics (1963). Since then, her work has been defined by an existential commitment to poetry and the visual abstractions of movement and light, which Lijn explores through pioneering works that combine concrete poetry with kinetic sculpture and experiment with industrial plastic polymers, Perspex, and acetic acid.

Driven by an interest in archetypes of female deities, Lijn began in the early 1980s to formalize her research on goddesses in Greek and Hindu mythologies. In her studio, Lijn transformed these iconographical references into monumental robotic sculptures that employed industrial metalworking, periscopic prisms, and electronic sequencers to summon the poetic and intimidating presence of hieratic sci-fi statuary. It is in this period that Lijn realized Electric Bride (1989), a large sculpture made from compressed flexible mica and a handblown glass head covered with cock feathers. Encased in an expanded metal enclosure connected to a 100-volt electric current, Lijn’s bride intones a poem whispered by Japanese pop-rock singer Shirai Takako, well known in the 1980s for her act with the band Crazy Boys.

The kinetic sculpture Gravity’s Dance (2019) continues this investigation thirty years later. Here, a swirling figure materializes from a textile skirt activated in a climactic spinning motion. The revolution of the work speaks to cosmic forces that mobilize matter and spirit, evoking at once the gravitational forces exerted by black holes, the ecstatic whirl of Sufi dervishes, and the Buddhist prayer wheels that inspired some of Lijn’s early kinetic works.

Liliane Lijn, Electric Bride, 1989, aluminum, steel, cock feathers, Elmflex micanite, brass, blown glass; 280 x 300 x 240 cm, courtesy the artist and Rodeo, London / Piraeus