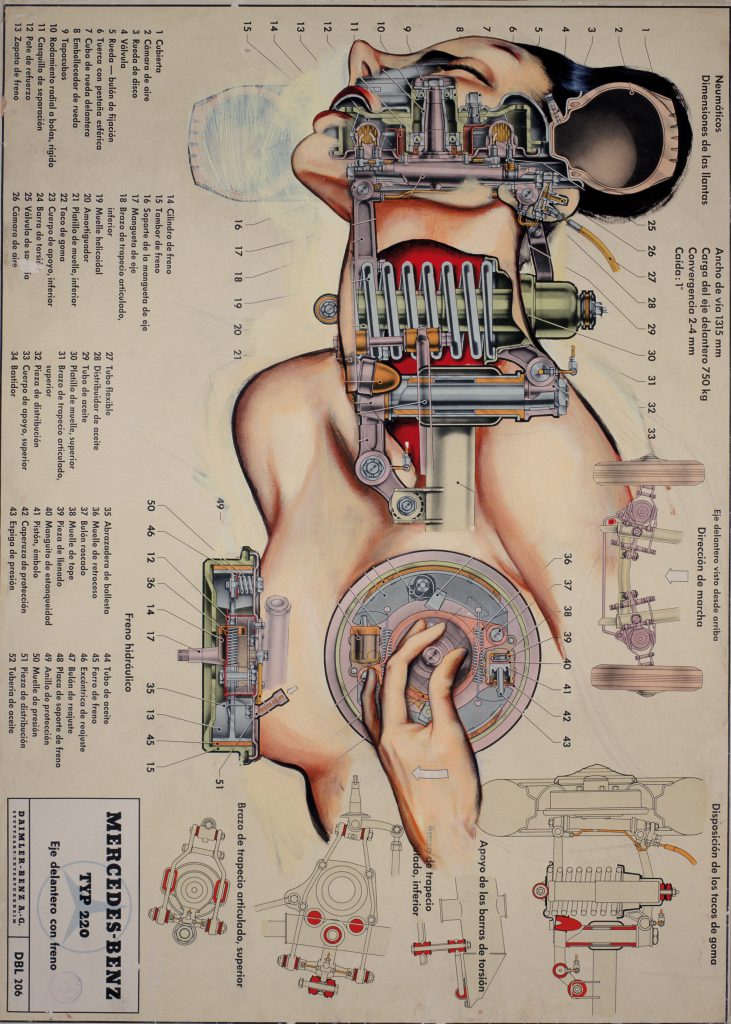

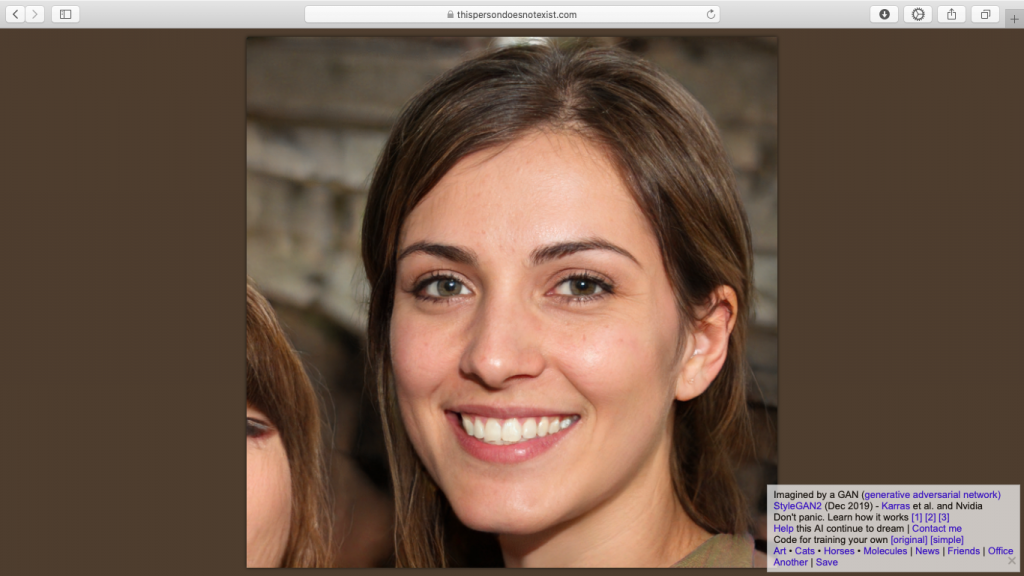

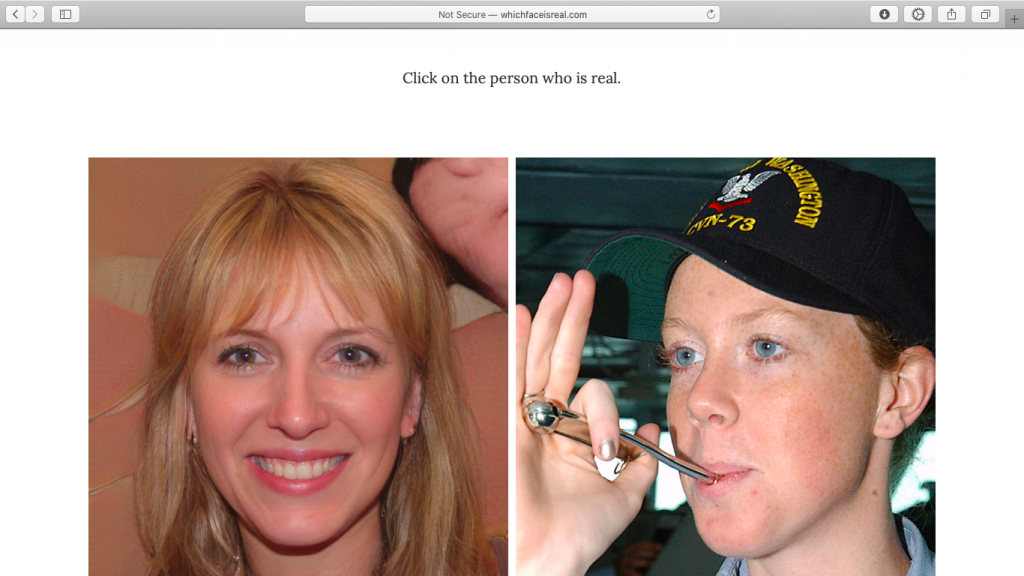

Millions of images float around between our phones, data centers, social media clients, and messaging apps all the time, every day. Just as we are constituted by biomes,3 so too are we by volumes of data, ours and from the planet and things on it, that pour into and out of data centers. All our Instagram filter-captured duckfaces make us database superstars. They also verify of our “real” identities, and populate training datasets for styleGAN techniques to create fake, diversity-appropriate, faces.4 Like blood, sweat and tears, our bodies give off data captured by digital moon cups: apps, social media, Fitbits, ovulation apps. The flurry of (meta)data keeps the internet turning and profitable. Information just wants to be free, apparently. As do we, from flesh and steel.5 Machines are trained to shape what news we read, culture we consume, jobs we get, sex we have. Bots even help us navigate harassment and sadness.6 And hetero-petro-capitalism is the crazy glue—or horror movie goo—that holds this all, us all, together. We are told that we are “free” to have a voice and speech online, but not flesh; “community standards” police our nipples and blood, but only selectively regulate our speech. The internet is a real place and what happens there is real. Its relationship to “meatspace,” or the place formerly known as “real” life, is a concern for institutional thinking built around the notion of a human who is real, reasonable (usually a cisman, a White man, a middle class, Upper Caste man) and not a being that is contradictory, partial, illegal, illegible, or unstable.

In this essay I bring together stories about the internet, and from theory, with those of several women like my friend and her friends. I want to put stories of bodily and digital regulation, duplication, sensuality, and defiance in conversation with work by Alexander Weheliye, Asha Achuthan, Coding Rights, Donna Haraway, Kéfir and Vedetas, Manifest-No, #MeToo, Nishant Shah, Ramon Amaro, Sara Ahmed, and Sarah Sharma, among others. Through them I think about the different tropes, hopes, metaphors, and material tactics for negotiating the pleasures and disappointments of our data flesh.

Think of this essay like being ample of bottom and wiggling and wriggling to create room and make space, as Sara Ahmed would have it,7 in small chairs in drab reception areas. “Sometimes that is what we struggle for: wiggle room; to have spaces to breathe. With breath, comes imagination. With breath, comes possibility.” Or as my friend says: “Why go down the path of predictable heteronormative coupling-possession, contractual obligations, NDAs? Don’t we have enough of that anyway?! It is either this, or being the victim of a leak. There has to be something else.”

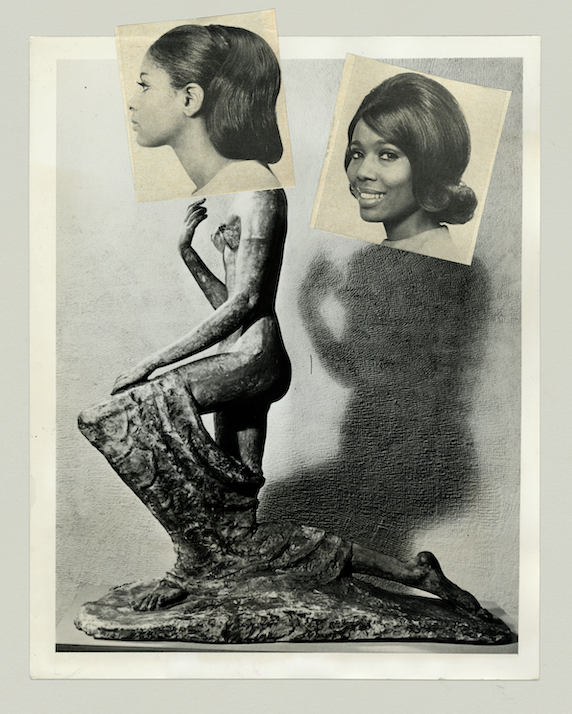

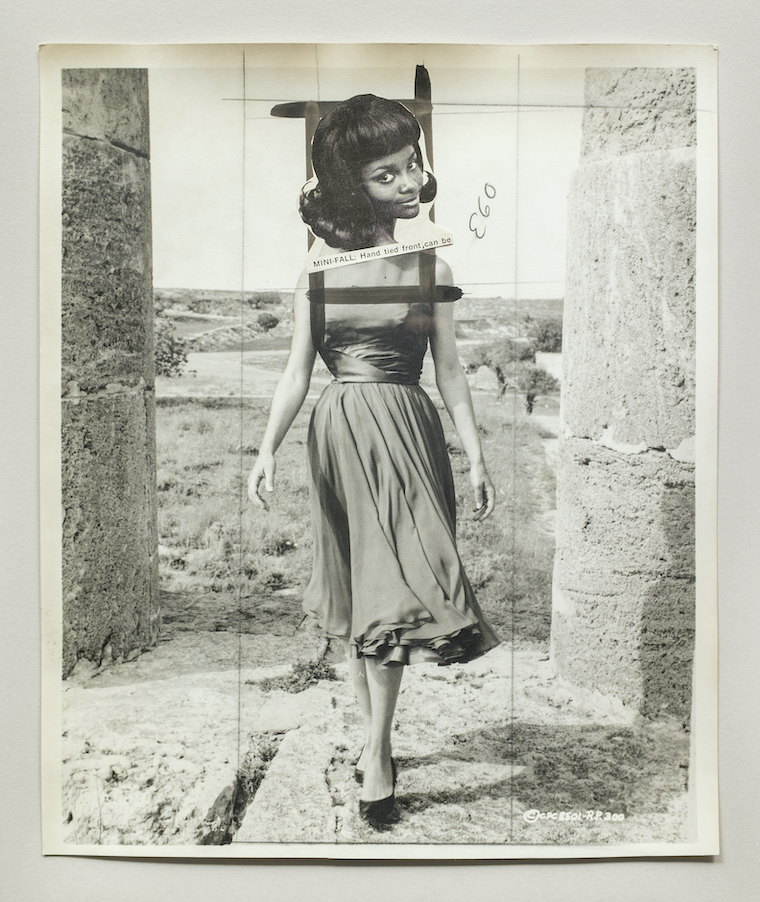

This story is about transformation of the human through the digital. But which human? Black Studies scholars like Alexander Weheliye8 point out that not so long ago, black bodies put on slave ships traveling across the Atlantic were deemed not-human, rather property; and artist Kodwo Eshun reminds us that they were the first moderns in their sense of “existential homelessness, alienation, dislocation, and dehumanization.”9 Similarly, across other seas, on plantations, and in cities, the bodies of black and brown “natives,” of queers, Dalits, and the differently-abled have populated our legal, socio-affective, moral and political orders as less-than-human. Technologies of measurement and quantification like the sciences, photography, phrenology, and physiognomy were developed to distinguish between “humans” and lesser humans. If we must talk about AI and the internet as potentially transforming the human, then we must acknowledge the history of this category of human-ness. The digital landscapes we live in are marked by this history, resulting in the inequitable distribution of highly automated, statistics-based discrimination and policing of different categories of humans. If we have to consider transformation, we might want to follow Ramon Amaro beyond the human-machine dialectic, who asks what an “aspirational black life” might be, and if it is possible to “gain a right of refusal to representation” through these systems.10 Like Bartleby the Scrivener, is it possible to refuse, firmly: “I would rather not” [be known in this way].11