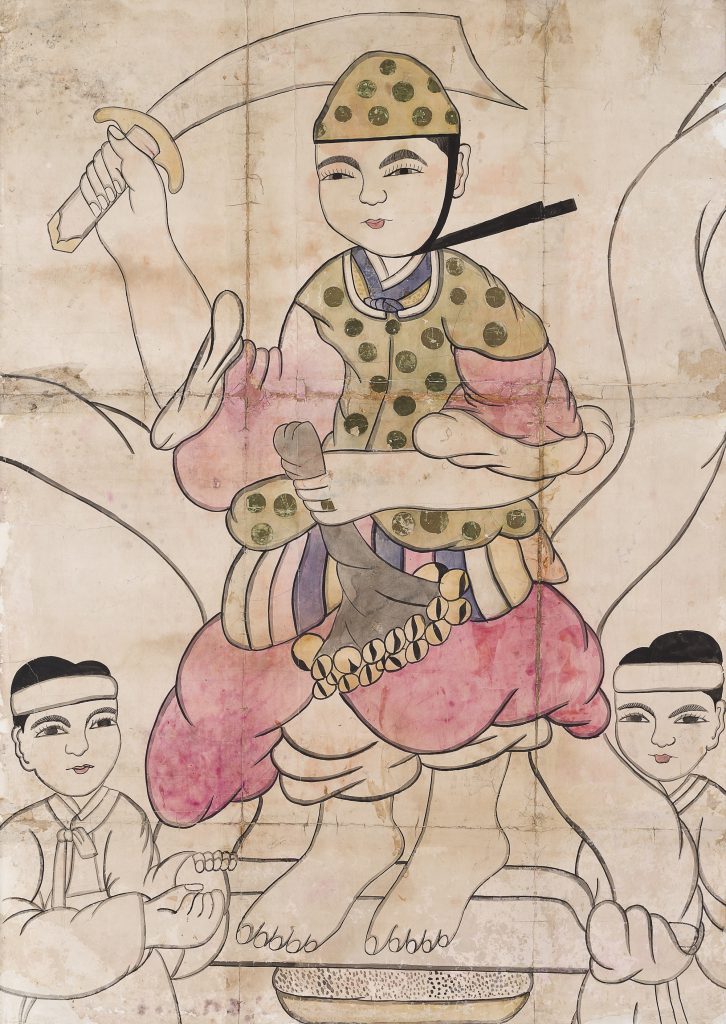

Imagine them away from a gallery wall. They were not made to inhabit a gallery any more than the elaborately worked ciboria in European museums were ever intended to leave a church. Imagine these paintings, these gods, in another place, grouped closely together in a narrow room, gods seated above an alter where candles flicker and incense wafts up to them. The mansin’s shrine room is a space apart from the ordinary, boldly colorful in ways disjunctive from the everyday, space commanded by the painted gods. This is where the mansin daily petitions them, requesting a clear flow of inspiration for the work she must do. When a mansin performs kut, she is enabled (or should be enabled) by the flow of divine inspiration, myônggi, literally “bright energy,” that comes to her through the paintings, through gods seated in the paintings. Inspiration enables her to make the gods present in words and action, opening the gates of fortune to her clients and chasing unclean and inauspicious things from their paths. It is her ability to call forth of things from out there, or when inspiration is illusive, to accurately improvise them, that makes the mansin’s work a living practice. Her gods address the problems of the floundering restaurateur, the child who has racked up credit card debts, the wayward spouse. The gods arrive in antique dress but in a living shaman practice, they engage a twenty-first-century moment.

When the dead appear at the kut—proper ancestors but also dead spouses, siblings, and children—the mansin gives them voice with tears and occasional bursts of humor. These encounters are intended to purge grief and maintain connection by stirring memories to an active state. The mansin’s ritual work of placating dead souls, most vividly and painfully those who died young, violently, or with other grievance, has given South Korea a powerful medium of political theater, an enduring legacy of the pro-democracy struggles of the 1980s. Mansin, and actors in mansin mode, have brought forth the massacred citizens of Gwangju, other martyrs of democracy and labor rights struggles, military “comfort women” conscripted as sex slaves for the Japanese Imperial Army, the schoolchildren left to drown on an illegally overfreighted ferry, and other victims of South Korea’s tumultuous modern history.

As with those we call “shamans” in other places, becoming a mansin begins with an involuntary calling; the prospective mansin suffers mysterious illnesses and misfortunes, vivid and disturbing dreams, and madness. Typically, naerin saram, or god-descended people, and their families struggle against the calling, a difficult path and in the past, an outcast profession. Once initiated, the new mansin begins a long process of cultivating her relationship with her gods as well as learning the complex pantheon and the business of chants, offerings, and performance through an apprenticeship that is not only difficult but sometimes exploitative. The mansin is not a spirit medium and she is not “just” a performer. Mansin do not experience inspiration as a one-on-one possession in the manner of a spirit medium; they are not vessels to be filled with divine presence; they are not puppets moved by invisible puppet masters. Mansin do claim that they are sometimes so powerfully taken over that they move and speak beyond their own volition. Initiates describe how extraordinary divinatory words burst out of them, proof of their strong connection to their own momju, or body-governing gods (who have chosen them for the unavoidable destiny of a becoming shamans). But doing the work of a mansin from day to day and kut to kut also requires a disciplined, skilled, and knowing sense of how to perform a kut. In the mansin’s view, this means not only mastering the expected and appropriate theatrical business of a kut but more profoundly, as a work of inspiration, understanding the gods’ and ancestors’ intentions and accurately translating them into words and gestures, such that the clients engage these beings as an active presence and harmony is renegotiated between them. Or as the anthropologist sees it, when the mansin is sufficiently skilled and sufficiently inspired, the clients experience an emotionally satisfying ritual process. However strong or weak the message, the mansin must convey the god’s intentions to the client during the kut. If she fails, both she and her client will be punished by angry gods.

Bright energy charges a mansin to do the gods’ work, but energies can ebb and flow, as does the relationship between a mansin and her gods. A mansin invokes her gods daily, making offerings in front of the painted images in her shrine where she also makes small rituals for clients and sometimes performs kut. In front of the god pictures, she asks for her gods’ assistance when she leaves the shrine to perform kut in other places. Mansin who carry the tradition of Hwanghae Province (now in North Korea), fold up their painted gods and carry them with them to kut, thus paintings once used by Hwanghae mansin have characteristic creases in them.

Inspiration reaches a mansin through the paintings and more powerfully when she encounters divine energies concentrated in sacred places on high mountains. She carries these energies back to the shrine and the images above her altar, in effect recharging her batteries (they also use this metaphor). A mansin who is favored by her gods receives a clear and strong flow of inspiration. A mansin who performs effective kut and gives astute divinations is recognized as enjoying the favor of powerful personal gods; the gods make her work efficacious. This, in turn, brings her many clients and she marks her gratitude with a well-fitted shrine, fresh costumes, and abundant offerings. A beautiful shrine testifies to a powerful and efficacious relationship between a mansin and the gods she serves. Alternatively, a mansin may offend her gods either by impure actions or by some inadvertent ritual lapse. Her flow of inspiration becomes staticky; she may hear only grumbling or weeping rather than words and lack visions or other intuitive signs. She experiences other misfortunes, a sudden falling off of business or a nagging illness, until she determines the source of the gods’ displeasure and sets things right. In extremis, angry gods depart, leaving empty paintings and silence in their wake. And some paintings may never be inhabited; initiation rituals fail where gods do not favor the aspiring mansin or where the gods themselves are weak.