In early medieval Europe, meanwhile, authors of romances indulged their zaniest dreams for self-moving mechanisms that imitated bodies born of nature. Some of these automata took the form of animals or birds and some resembled humans, only they were better and more exciting. For historian Minsoo Kang, such uncanny creations explore essential questions about the human-as-machine. In Sublime Dreams of Living Machines: The Automaton in the European Imagination, Kang notes that the automaton is a “conceptual tool with which Western culture has meditated on both the possibilities and the consequences of the breakdown of the distinction between the normally antithetical categories of the animate and the inanimate, the natural and the artificial, the living and the dead.”9 Fast-forward to 2011, and South Korean artist Wang Ziwon is beginning to assemble electric machines in the shape of buddhas and bodhisattvas.

Personhood and Thaumaturgy

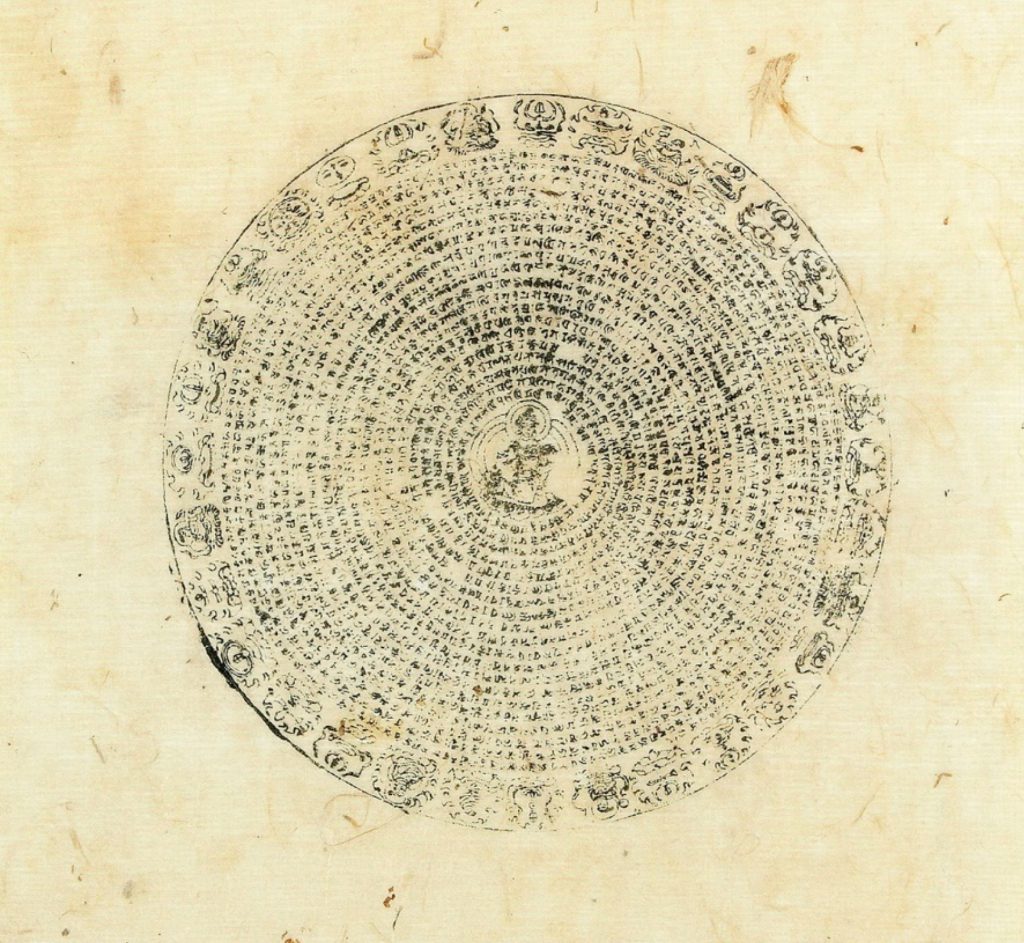

Buddhism is a sophisticated religion and philosophy with an extensive body of doctrines. The form of Buddhism prevalent in Korea, Japan, and China, Mahāyāna Buddhism, does not distinguish between immanent and transcendent realms. For many Mahāyāna Buddhists, it is not only sentient but also insentient beings that possess “Buddha-nature.” In other words, the Buddhist doctrinal framework in which robots such as Mindar can be perceived as manifestations of the bodhisattva Kannon/Gwaneum/Guanyin does not separate transcendence from immanence. The texts that inform Mahāyāna Buddhist thought posit that the realm of the divine and the realm of the worldly permeate each other. This non-dualist and non-essentialist thinking has permeated daily practices for centuries. As Buddhism spread from India to other parts of Eurasia over the course of the first millennium, its texts and practices were important vehicles for the cross-cultural dissemination of ideas. Crucially, Buddhist teachings contain a core precept for which there was no equivalent in native Chinese and Korean traditions: upaya or “skillful means.” This principle prompted believers to use whatever means they deemed appropriate to ensure the salvation of all kinds of living creatures. Central to the teachings of the Korean Buddhist school Hwaeom and the Chinese school of Huayan is the idea that all things have their place within the harmony of the universal order. The bodhisattva—anyone who seeks enlightenment not only for themselves but also for the sake of everyone else—reaches enlighenment by advancing through ten different stages of achievement, and acquires thaumaturgy on this journey so that she can bring the cosmos together and deliver beings from suffering. Following Buddhism’s cue, transhumanists in the West conceptualize a non-anthropocentric theory of personhood. Wherever there is personhood—in viruses or bacteria, fish or chickens—it should be respected.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Buddhism also emerges as a major factor in medical and health-related discourse on a global scale. Rather than being wholly replaced by biomedicine in modern Buddhist societies, rituals, meditations, and other healing practices have continued to play a significant role in health care. While Buddhist medicine was challenged by intensive modernization and secularization, in 1963, the Supreme Court of Japan ruled that Buddhist healing rites could be called upon as complements to modern biomedical treatments.10 Some Buddhist therapies—particularly meditation for alleviating ailments associated with stress—are also beginning to be taken seriously by neuroscientists, psychiatrists, and by other branches of biomedicine.

Technologized Futures

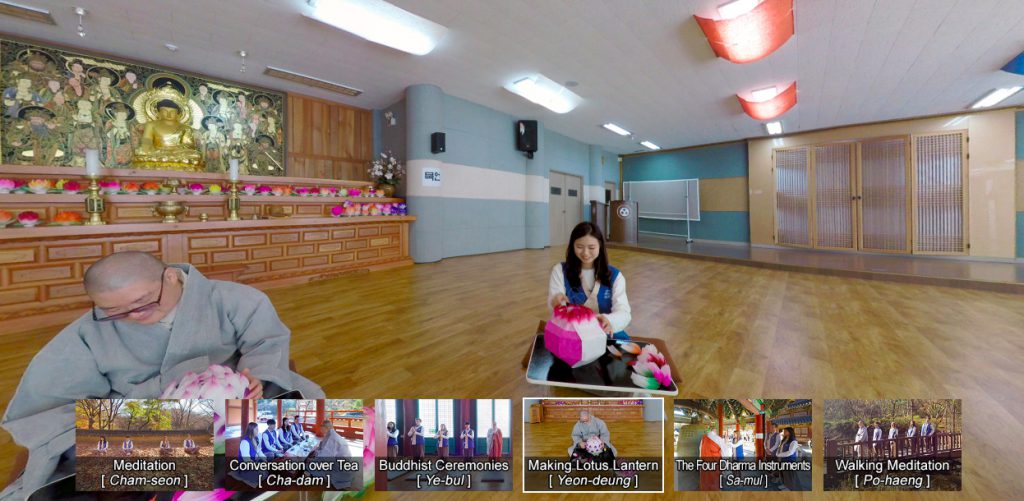

As we theorize media and mediation, we must engage with the many modes in which technology and digital media are understood, adopted, and used vis-à-vis earlier practices. What we refer to as “religion” and “technology” can function in surprisingly intimate ways and form coherent arrangements of social and cultural practices when deliberately intertwined. They involve and mobilize epistemological and cosmological questions of the constitution of the real. In the context of cyber-Buddhism, practitioners use various media forms (visual, aural, and haptic) and refashion and filter them through a modern Buddhist sensibility. They create new senses of the self and its surrounds, both social and built. Cyber-Buddhists facilitate exchanges of religious ideas and objects, and increasingly participate in the flow of information, images, sounds, social ties, and commodities. While the fetishizing of material things for spiritual ends is not new to capitalism, this has now taken on new characteristics. Buddhists can use all manner of pious commodities—portable, wearable, and electronic—to defy discrete conceptions of materiality by constructing piety and virtue through commodification and consumption rather than outside of them. Religion and technology do not exist as two ontologically distinct spheres of knowledge and experience. On the contrary, modern communication technologies and Buddhist technologies of salvation can be combined in the realization of religious presence. For Buddhist clerics in China and Korea, the computer monitor, the internet browser window, and, above all, the smartphone screen, create novel public spaces. In China, these transformations have occurred against the backdrop of the post-Mao market transition. Regional capitalist development enabled by post-Mao reforms has largely depoliticized local faith practices. For the state, the growth of information and communication technologies and the informatization of political economy and social life are of the highest strategic importance. High-tech expansion buttresses the political dominance of the Chinese Communist Party and its project of modernity. The cyberspace of Chinese Buddhists is one part of the larger electronic infrastructure of China’s market economy. Many people have pointed out the entanglements between the materialism of contemporary China, the social dislocations caused by neoliberalism, and the moral yearnings and ethical aspirations of some urbanites. Such yearnings are reflected in the worlds of Buddhist-inspired social media that, at least for the time being, have opened up spaces and opportunities for self-making, and have granted unprecedented access to religious knowledge and monastic networks.