It is possible to consider these practices not in terms of being conditioned by Freudian bourgeois drives, but as easy alignments with desire. At around the same time as the exiled Russian anthropologists were making their observations of the Chukchee, Freud was theorizing the sexual desires of European man in relation to the Greek tragedy of Oedipus. A scarcity of objects—and therefore fixations conditioned by consumerism—made the peoples of the Far East much less likely to use things as mere props in their domestic dramas. Objects were rare: things became active, had agency, could not stay inanimate. This is not to say that there was no material inequality before the Soviet administration took over Chukotka. Bogoraz, along with other socialist observers, always attentive to the make-up of society, recorded poorer Chukchee pandering to richer members of the tribe by carrying out small chores to ingratiate themselves with the local oligarch. There was also notable disparity in endowing creatures and objects with personhood. All things in contact with the spirit world were considered sentient. (Bogoraz relates one memorable example: a tale of the excrement of an evil spirit come to life.) Most animals and plants were also considered to have equal minds, and could enter into sexual and social unions with humans. Notable exceptions were deer and walruses, which had no rights in the Chukchee’s moral universe, unlike whales or foxes. The personhood of animals and plants did not depend on whether they were the basis of local economies. Sometimes animals could both be objectified and retain their subjectivity, as in a fairy tale about a seal who was made into a lamp while continuing to communicate with other animals and humans. Bogoraz reports that the birch tree was seen to be neutral and so was treated unceremoniously. Throughout these tales, it is clear that what was construed by the civilizing missions of the Russian Empire and the U.S.S.R. as a struggle with nature was for the Chukchee a form of respectful inaction.

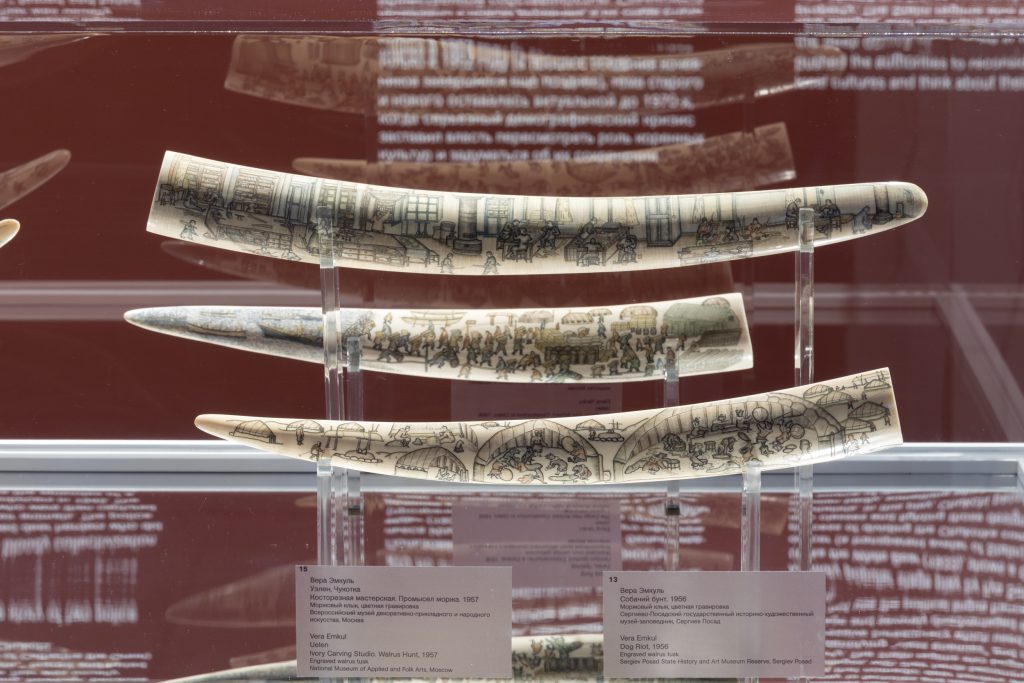

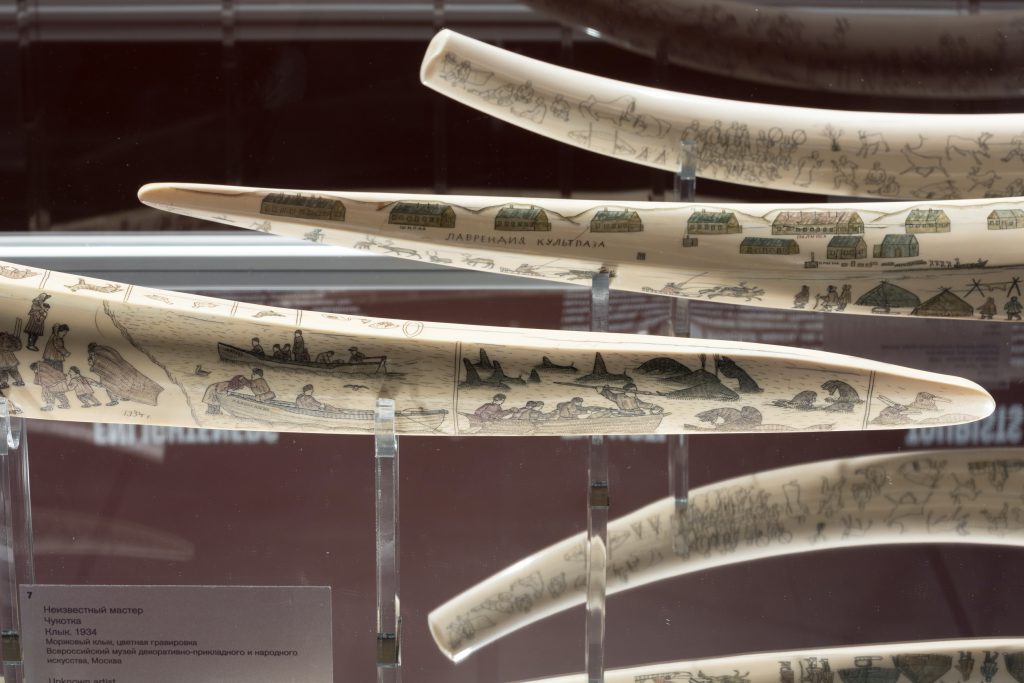

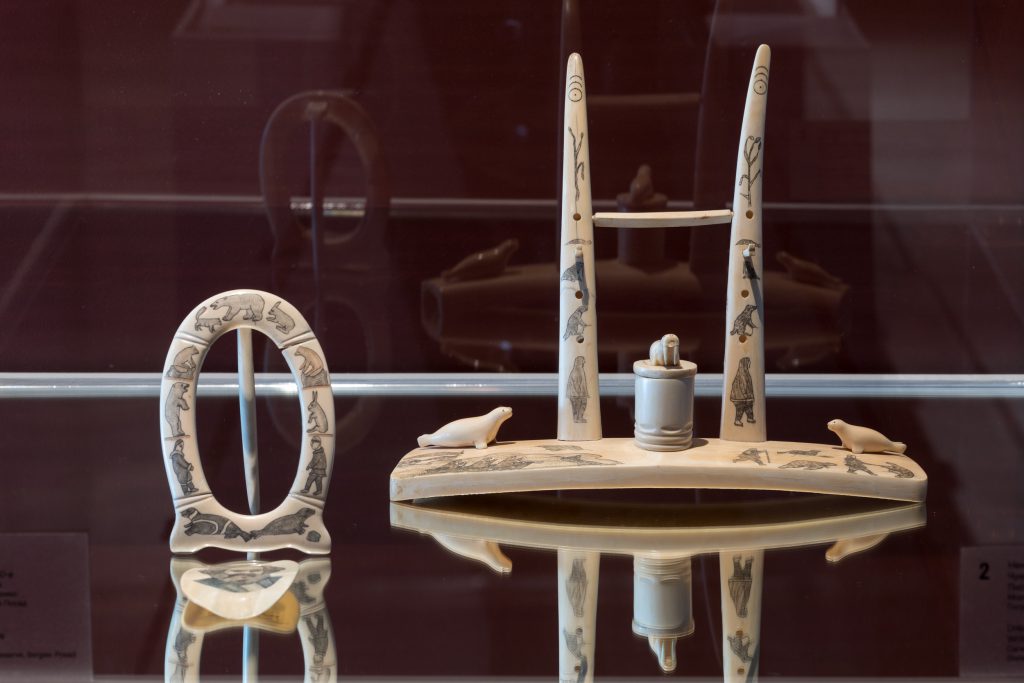

Little remains of all these forms of sexual and biopolitical creativity in terms of visual or textual evidence after the 1930s. Moreover, indigenous kinship between man and animal was almost the only type of non-heteronormative relationship to be widely depicted by Chukotka’s artists, who carved scenes of local life on walrus tusks. Carving first appeared in the form of souvenir additions to trade deals with Russian and American sailors. Intricate scenes show the Chukchee’s familiarity with manga, which had been prominent since the mid-1800s in Japan. It is possible that manga prints ended up in Chukotka via sailors, but there is no evidence of this as paper quickly deteriorates in the weather conditions of the region. In the 1930s, tusk carving was subsumed under the Soviet artistic unions that controlled art-making, yet some artists still found a way to convey anti-imperialist messages, depicting comrades who had killed themselves or disguising anti-Russian folk stories as animal fairy tales.

Whether in the 1840s or one century later, colonial rule was remarkably consistent, with important conceptual links between modes of governance. According to Johann Gottlieb Georgi, author of Geographisch-physikalische und naturhistorische Beschreibung des Russischen Reichs (A physical and natural history description of the Russian Empire, published in Germany between 1797 and 1802), the range of peoples in the Russian Empire represent “the World in all the stages of transition to the modern World, refined and enriched by needs.”11 Georgi discerned three of these stages, the first being hunting and gathering; the second, nomadic shepherding; and the last represented by agriculture, which spread from “early cultivation to complete perfection.”12 One might think that the October Revolution of 1917 would end the incessant progressivism of world history scholars and policy makers—and it did, albeit for a limited time. At first, policy makers, inspired by the active representatives of pre-revolutionary socialist anthropology, decided that most peoples of the Russian Far East live in a classless society, where whole populations can be thought of as one exploited class. In an introduction to Bogaraz’s aforementioned book on the Chukchee, published in Russian in 1934 after several American editions, the author had to adapt to the times and exchange his previous Progressivist outlook for something more aligned with revolutionary sympathies with the Empire’s victims. His view now was that the Chukchee constituted an example of “primitive communism,” a hypothesis that had already been put forward by Lev Shternberg more than twenty years previously. Bogoraz underlined the concept of “comradeship” as crucial to the Chukchee’s way of life, giving examples not only of the group marriages of “comrades-in-wives,” but also of the custom of calling dogs and smoking pipes “comrades-in-boredom.”13

By the mid-1920s, Stalin’s tactics in Siberia and the Far East were seemingly designed to prove historian and philosopher Oswald Spengler’s global pessimism right. “Hard as the half-developed Socialism of today is fighting against expansion,” Spengler wrote in the 1922 edition of The Decline of the West, “one day it will become arch-expansionist with all the vehemence of destiny.”14 “Vehemence” is an apt word to describe the relentless search for bourgeois exploiters during the Stalin years. “At the time of the ‘intensification of the class struggle’ one had to find class enemies or face the risk of becoming one,”15 historian Yuri Slezkine wryly notes. The Soviet power was set on destroying nomadic ways of life and turning all Far Eastern peoples into collective farmers, while another prominent Socialist exile, Sergey Mitskevich, pronounced these projects “crackpot bureaucratic scheming … laughable enough under tsarist regime.”16 Journalist and researcher Vitaly Zadorin, based in and around Chukotka since the 1950s, noted that the 1960s were the era of the Soviet Union’s last significant effort to redraw social maps of the region through transforming nomads into settlers. “Many have thought that new settlements can concentrate the nomadic population, create a distinct social infrastructure, and free the people from the struggle for survival,” writes Zadorin in an overview of the U.S.S.R.’s post-war policies.17 However by the mid-1980s, life expectancy among the settled part of the Indigenous population was forty-two to forty-four years old, even lower than that of the pastoralists.18 The 1990s were a time of extreme poverty and separatist movements. At present, thanks to large-scale private investment in the region during the 2000s, several Indigenous practices (such as whale hunting and shamanic ritual) are preserved, while non-heteronormative relationships are largely kept hidden, as the current Russian “law on gay propaganda” dictates. Soviet progressivism in the end placed the nuclear heterosexual family as an obligatory stage of societal evolution, so that queer, more fluid alternatives are mostly consigned to historic reports.