Udmurtian Family Tokens

In Izhevsk, the capital city of Udmurtia twelve hours on a slow train from the Ural Mountains, the regional museum exhibits the cultural artifacts of the Udmurts, a community of Finno-Ugric language speakers. Among them is a series of tokens, Udmurtian family signs.

The museum’s archeologist told me that these family signs are related to property and possession: if someone finds a tree with wild bees in its hollow, they mark it with their family sign so that the tree becomes their property. The tokens are used for marking land and animals; on traditional fabrics, carpets, and even gates. During the building of Izhevsk factory in the Soviet era, the signs were used to mark the execution of work. They were also used as signatures on documents, and could be sold as part of the property—you sell the sign, you sell the property.

The origin of family signs goes back to the names of the mothers of the female prophets who protect a clan. They are amulets. While the family tokens still function as a substitute for money, the exchanges they facilitate encompass something beyond money’s function: not a standardized unitary measurement of value, but the histories, stories, and sensations that circulate around families. Family tokens can also be carved onto trees, designating natural resources as something between private custodianship (not actual ownership) and the commons. The abundance of trees in the Siberian taiga makes this non-monetary “wealth” prolific; with this practice, responsibilities toward nature and the community at large are also marked.

Legends have it that in the past, all family signs were known by every Udmurt. As a result of punishment from the gods, people now only remember the sign of their own family. What would their society have been like when everyone knew every family token? Were exchanges then based on different principles; or can they even be characterized as exchanges? The subjects engaging in exchange-like activities would have been very differently constituted.

After anthropological studies on the gift economy of traditional societies, value can be traced as starting with the inalienable circulation of things among “dividuals” through money-mediated, alienated transactions among individualized agents. The exchange of family tokens would have likely looked more like ritual than exchange, enabling as it did the passing and assuming of various roles and functions in the community through its performativity. The parties involved were dividuals, not mutually foreign individuals. The performative constitution of roles, rather than individual identities, is the key to building intricate ties that hold a community together over time. In this sense, the gift exchanged is not a medium of transaction but an index of sociality.

Again, this index is decentralized, and moreover, distributed, in that everyone engaging in community activities belongs to the same index, which arranges who gets what and how—by taking on which temporary roles. One could call such a social form a “pre-modern blockchain,” for the contemporary development of the blockchain maintains the veracity of a log of global transactions, not by creating a centralized auditing authority but by distributing the log so that every participating node has a copy of the same ledger. Although analogous to the everyone-knows-everything social form, this is an automated computational process, and hence without the affect and performativity of embodied community making. In a way, the pre-modern exchange of family tokens performs a ritualized commons, built not on the shared ownership and stewardship of resources by individuals, but as a growing social index of exchangeable roles in an ever mutating society.

Kulay Cauldron

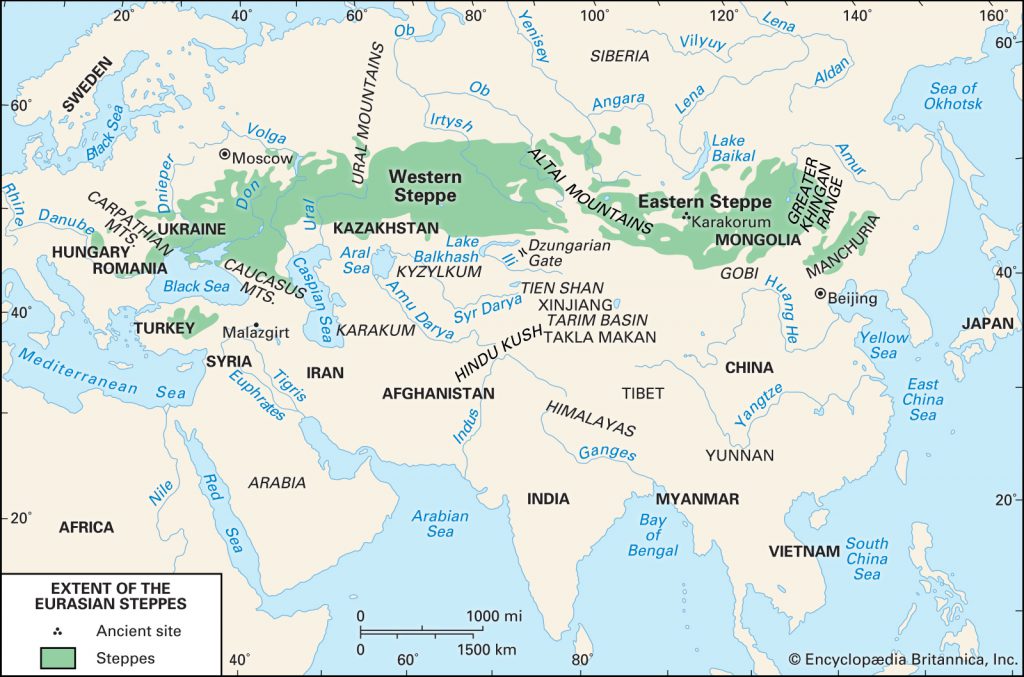

Movements and transformations take place both physically and metaphysically. Often, the former overshadows the latter. Throughout Eurasia, I have encountered metallic jewelry and ornaments produced by historical nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples of the steppes. In the local history museum of Tomsk in Siberia, I came across objects made from bronze, crafted by people of the Kulay culture between 500 BCE and 500 CE. One object was particularly interesting: a small cauldron for casting metal. It is a meta-object that conditions the production of all the other bronze objects. The nomads, write Deleuze and Guattari, attached:

fibulas, gold or silver plaques, and pieces of jewelry … to small movable objects; they are not only easy to transport, but pertain to the object only as object in motion. These plaques constitute traits of expression of pure speed, carried on objects that are themselves mobile and moving.

The continuous motion of travel and the constant necessity to recast according to needs place the objects beyond the fixed form and content of art history’s records. These objects instead existed in a process of mutual mutation and rebalancing of material elements. Keeping this idea of being part of a continuous flow of matter and energy in mind, as well as the idea of how the process of individuation works as a metaphor for the social, we might ask: What if the individual is not conceived as a discrete entity, but rather as a changing composite of social forces? How can one meaningfully engage as part of a larger community beyond individualist interests, without being struck by a fear of losing oneself? And indeed, why, in the developed capitalist world, are we afraid of losing ourselves, when in contemporary society, we seem so lonely?