The crisis posed by the Covid-19 pandemic now gives the question of understanding social media new urgency, in ways that even Marshall McLuhan’s prophetic Understanding Media (1964) could not have foreseen. How might the epistemological confusion stemming from social media contribute to social and political confusion? Information and disinformation have become deeply entangled, like host and parasite—only without the benefit of knowing which is which. In a worst-case scenario, being well-informed also means being misinformed, as William Burroughs alluded to when he said that “sometimes paranoia’s just having all the facts.” One current example of the imbrication of information and disinformation—which might be a comic soap opera if it weren’t for the fatal consequences—is the American political right’s refusal (along with similar sentiment in other Western democratic countries), against medical advice and factual evidence, to wear face masks, because they see the mandate to wear masks as a violation of their individual rights and freedoms, a descent into socialism. Hence, the refusal becomes a patriotic defense of America, in spite of the fact that this can contribute to a drastic increase in the US death toll. A fanatical commitment to liberties overcomes common sense around health.

Former US President Trump led the Covid confusion, fond of both junk-food and tweeting, and equivocating on the wearing of face masks. Until the eventual suspension of his Twitter account in January 2021, he exploited this and other platforms to diminish, for political reasons, the seriousness of the virus and delay the country’s pandemic response. It could be said that this fatally delayed response, communicated chaotically via media, is another kind of virus, an informational virus working alongside the biological virus to further its propagation. The disinformation is passed on to Trump supporters, who repeat his denial of the epidemic’s seriousness, or even its existence. In South Dakota, a state that tested a staggering 60-percent positive, Republican governor and Trump ally Kristi Noem can say, “My people are happy because they are free,” while people keep dying in hospitals filled beyond capacity. A most harrowing detail, as frontline nurse Judi Doering reported on YouTube and indeed on Twitter, is how as these patients lie dying, they often remain in denial, gasping with their last breath: “This is not happening, this is not real.”

Has social media made “the real” disappear? Is it the loss of a sense of reality that makes so many people deny, even when biological life is at stake, what seems so clear to everyone else? In October 2020, Berlin-based South Korean theorist Han Byung-Chul published a highly controversial essay on the pandemic, “Why Asia is better at beating the pandemic than Europe: the key lies in civility.” Han begins by asking not why America and Europe have handled the pandemic so badly, but why Asia has handled it so well. His answer, rightly criticized for its essentialism, is that Asia is more accepting of authoritarianism because of its Confucian culture. Hence its politicians and peoples do not put up much resistance to digital surveillance or to wearing masks, both of which have proved effective in containing the coronavirus. Essentializing Asia goes together with essentializing the West, so that the refusal to wear masks is seen as a form of individualism. However, this individualism proves to be a more extreme if tacit form of obedience to authority—an obedience to seductive, powerful leaders to the death.

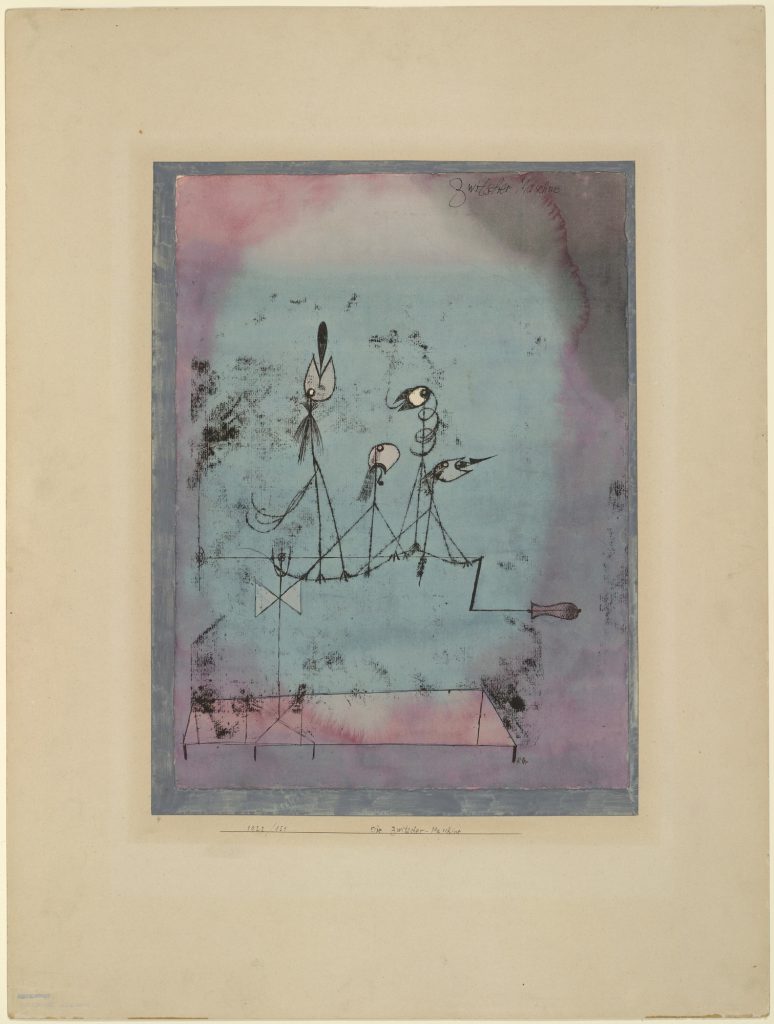

Next, and somewhat more convincingly, Han argues that digitization and “fake news” have eliminated reality, and that what the pandemic represents is the shock return of something “natural”—not just a computer virus, but a real virus, which a culture overdosed on a diet of virtual reality cannot handle. The idea of the pandemic as “the return of the real” is also a little misguided, because it maintains an opposition between actual and virtual worlds, where one is real and the other is delusional. It is, in my view, more exacting to begin by saying that at this moment in media history, both the virus and social media are real. There is no “return of the real” because the real never disappeared. What has become obsolete is the old divide between actual and virtual, which predefines and so reduces both realms. We are confronted today, as ever, by a real that is ambiguous and entangled with difficulties, a nondescript, indiscernible real: our real. When Klee asserted that art does not reproduce the visible but makes visible, we might understand him to mean that art engages with a real that is under no obligation to conform to our notions of it.