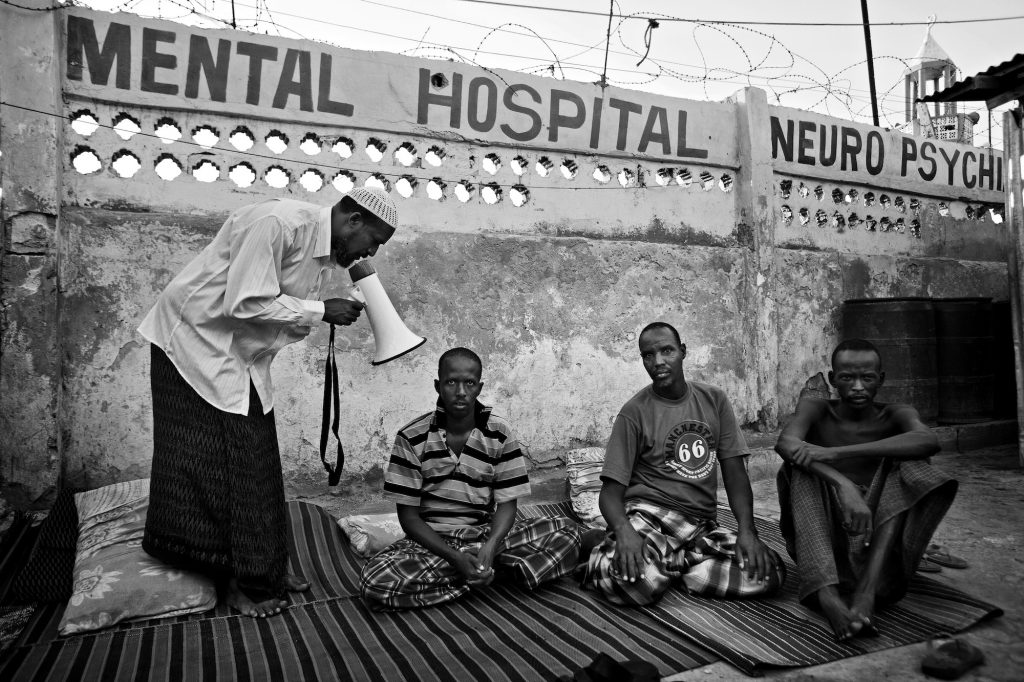

While the discourse around mental health is welcomed by many practitioners in the MENA region, there are some limitations in terms of how it is understood. The issues of reliability and consistency fail to account for neurodivergence across different cultures, revealing the ethnocentrism of the DSM, and its inherent bias against non-Western people. Mental illness is a spectrum of neurodivergence, with 971 million people worldwide suffering from some kind of mental disorder. From a genetic perspective, mental illness is polygenic, meaning that there are, for example, forty-four gene variants that raise the risk of depression. There are life experiences that compound the risk factor for mental illness such as abuse or trauma.

Although the specific and dynamic (hi)stories of the Middle East are important for the questions at hand, so too are the wider global narratives that shape disease. What role do medical narratives have in shaping our understanding of international diseases and how do these align with the shifting definitions of disease today? “Psychiatric disorders are increasingly widespread in the Middle East,” remarks Mohammed Yahia in Nature Middle East, “however, the model used to assess and treat patients in the region was developed by a primarily Anglo-Saxon population based in the United States and Western Europe.”11 Yahia underlines that there are a set of material and social concerns that account for psychiatric disorders. Moreover, he argues that there are particularities of trauma, which are crucial to how we understand mental health in the Middle East and North Africa.

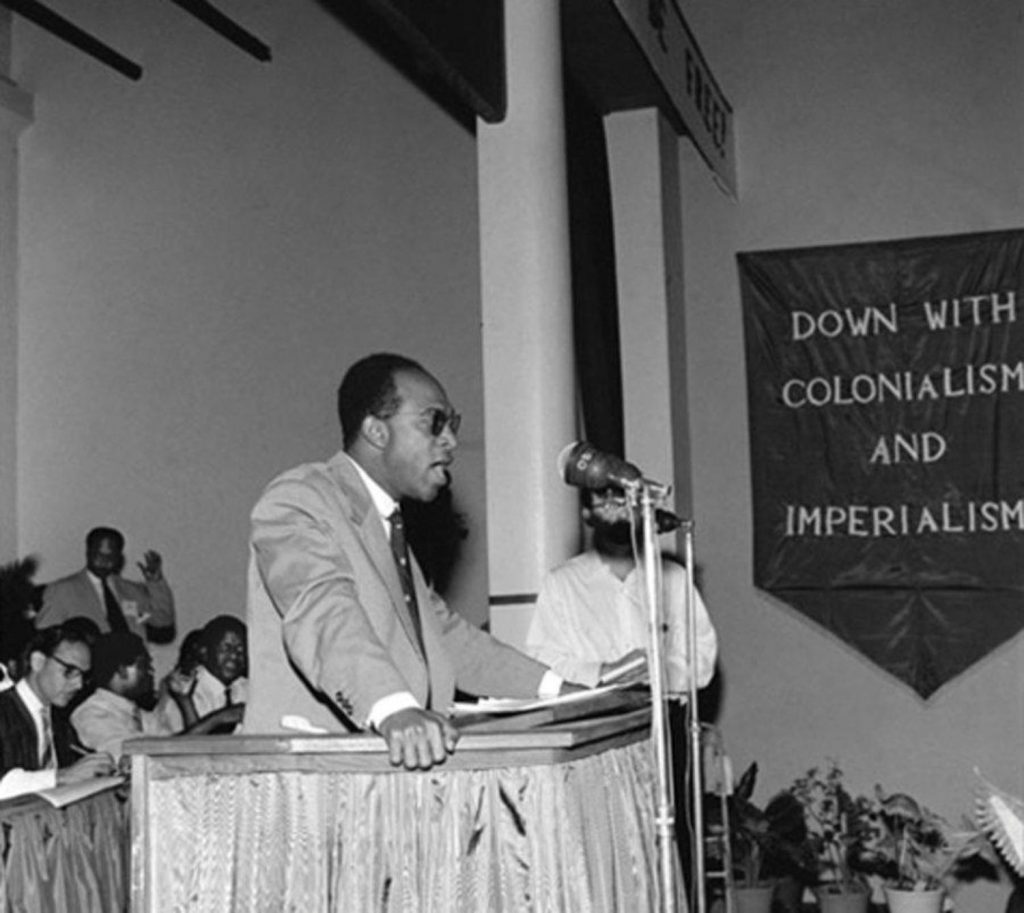

As Hanafy A. Youssef and Salah A. Fadi attest: “Frantz Fanon paid particular attention to these social problems and his brand of political psychiatry is as relevant today as it was during his time. Alienation and oppression still exist. Unemployment is widespread and tyrannical rulers still oppress their people. Mental illness cannot be solved by drugs but by changes in the political and social order.”12 What Youssef and Fadi are gesturing to is the necessity to approach psychiatry from a holistic viewpoint, in which we seek to understand society’s role in shaping mental illness.

Returning to the present day, it is clear that no country is immune from mental illness. Mental health data collectors report that countries that have been at war clearly suffer from a large incidence of trauma-related mental illness. In a pandemic, too, alienation can be strongly felt. The pandemic and its subsequent reshuffling of society exacerbates the structural differences brought by centuries of racial capitalism throughout the world. How we understand them, document them, and heal from them is the change that we need—the social mutation that is necessary for repair. The entanglements of medicine and power in the age of Covid-19 call for the globality of particular forms of medical expertise.

Amid the disarray of the immediate situation, even with an awareness of these global inequalities, the way privileged communities react to epidemics often depends upon varying degrees of empathy. This extends differentially to the sick and dying, to those who fall under the jurisdiction of the carceral state, and to those who do not. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, it warranted a call to action—a global shutdown, albeit one that saw uneven responses. Unfortunately, even in countries of the Global North, the spread of the epidemic exposed how microbial contagions mutate along the open veins of society, disproportionately affecting the poor and the disenfranchised. In this period of needless death, we must find a politics of reflection, a meditation on all the troubled yet path-breaking perspectives on mental health, and on what it would mean to afford the resources, energy, or triage for comprehensive care. Along with an epidemiological machine, tied to the rollout of vaccines, there should be more community-based intervention, and mental healthcare should be activated as a vital component for living in this fragile period. In this way, we might find new modes of contemplation and healing, and relevant ways to conceptualize the social aspect of the psychology of mental illness in the midst of a pandemic, so that more people may exist in the terrains of good health.